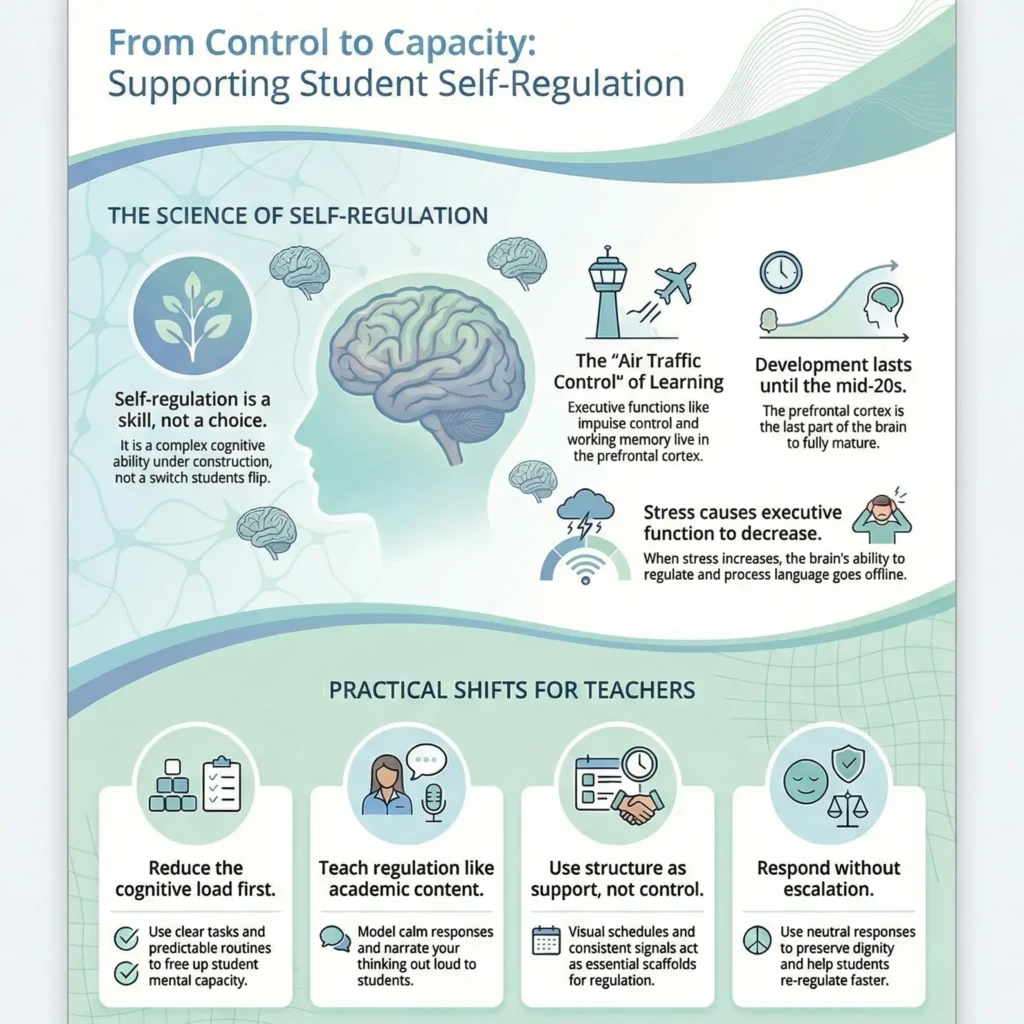

Self-Regulation in Students: Why Behavior Is a Skill We Must Teach

We often talk about self-regulation in students as if it’s a character trait.

“They should know better.”

“They’re old enough by now.”

“They just need to make better choices.”

But self-regulation is not a switch students flip on when they feel like it.

It’s a complex cognitive skill set—and for many students, it’s still under construction.

When we treat self-regulation as a moral failing instead of a developmental process, we respond with consequences instead of support. And that’s where classroom management quietly breaks down.

WHAT IS SELF-REGULATION, REALLY?

Self-regulation refers to a student’s ability to:

Manage emotions

Control impulses

Shift attention

Persist through difficulty

Pause before reacting

Recover after mistakes

These abilities live under the umbrella of executive function—the brain’s management system.

And here’s the key idea:

Executive function skills are learned, fragile under stress, and unevenly developed.

EXECUTIVE FUNCTION: THE “AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL” OF LEARNING

Executive function includes skills such as:

Inhibitory control (stopping yourself from reacting)

Working memory (holding instructions in mind)

Cognitive flexibility (shifting strategies or perspectives)

Task initiation

Emotional regulation

These skills are primarily governed by the prefrontal cortex—an area of the brain that:

Develops slowly

Is highly sensitive to stress

Is often not fully mature until the mid-20s

So when a student blurts out, shuts down, avoids work, or escalates quickly, it’s often not defiance.

It’s a temporary executive function failure.

WHY SELF-REGULATION BREAKS DOWN AT SCHOOL

Even students who can self-regulate in one setting may struggle in another.

Common classroom stressors include:

Unclear expectations

Frequent transitions

Social pressure

Public correction

Cognitive overload

Time pressure

Sensory noise

When stress increases, executive function decreases.

That’s why self-regulation in students looks inconsistent—and why “they can do it sometimes” isn’t proof they can always do it.

A CRITICAL SHIFT: FROM EXPECTING TO SUPPORTING

Traditional classroom management often assumes:

“Students already have self-regulation skills. They just need motivation.”

A more accurate assumption is:

“Students are still developing self-regulation—and the classroom can either support or overload that process.”

This shift changes everything.

HOW CLASSROOMS CAN SUPPORT SELF-REGULATION IN STUDENTS

Self-regulation in students does not improve through reminders to “try harder.”

It improves when classrooms are intentionally designed to carry some of the regulatory load for students.

Think of effective classroom management not as controlling behavior—but as building external supports until students can internalize them.

1. Reduce the Cognitive Load First

Before responding to behavior, pause and ask:

Is the task clear?

Is the routine familiar?

Is the environment predictable?

When students are overwhelmed, the brain prioritizes survival and emotion, not reasoning or self-control. If students must constantly figure out what they’re supposed to be doing, how long it will take, or what success looks like, their executive function is already under strain before behavior becomes an issue.

Reducing cognitive load means:

Giving clear, chunked instructions (one step at a time)

Avoiding last-minute changes when possible

Making routines automatic so they don’t require decision-making

Ensuring tasks are appropriately scaffolded—not cognitively overloaded

What this looks like in practice:

A predictable entry routine every day, even when the lesson changes

Written instructions that stay visible while students work

Consistent task formats so students don’t have to decode expectations each time

Clear time frames (“You have 7 minutes for this”) instead of vague pacing

When students don’t have to spend mental energy figuring out what’s happening, they have more capacity to regulate emotions, attention, and behavior.

2. Teach Regulation the Way You Teach Content

Self-regulation is not absorbed through osmosis.

It must be taught, modeled, practiced, and revisited—just like reading, writing, or problem-solving.

Students improve their ability to self-regulate when teachers:

Model calm, regulated responses—especially under pressure

Narrate their thinking (“I’m feeling frustrated, so I’m going to pause before responding.”)

Practice routines repeatedly until they become automatic

Pre-teach what to do when things go wrong

This might feel slow at first, but it saves enormous time later.

What this looks like in practice:

Explicitly teaching how to ask for help without calling out

Practicing transitions as a class (and re-practicing when needed)

Naming emotions neutrally (“It looks like this is frustrating right now.”)

Teaching students what to do if they feel overwhelmed, stuck, or upset

If we never teach regulation skills directly, we shouldn’t expect students to magically use them—especially under stress.

3. Use Structure as Support, Not Control

Structure is often misunderstood as rigidity or control.

In reality, structure is one of the strongest supports for self-regulation in students.

Predictable structures allow students to regulate without consciously thinking about it.

Examples include:

Consistent entry and exit routines

Clear, predictable transitions

Visual schedules or agendas

Familiar attention signals

Posted expectations using student-friendly language

These systems reduce uncertainty—and uncertainty is a major trigger for dysregulation.

What this looks like in practice:

Students know exactly how class starts, even if they’re anxious or tired

Transitions are signaled the same way every time

Expectations are stable across days and activities

Visual reminders reduce the need for repeated verbal corrections

These structures are not about compliance.

They are regulation scaffolds that quietly support students’ nervous systems throughout the day.

4. Respond to Dysregulation Without Escalation

When a student is dysregulated:

Reasoning is offline

Threat detection is heightened

Language processing is reduced

In this state, students are not being willfully difficult—they are neurologically unavailable for learning or reasoning.

This is the worst possible moment for:

Lectures

Public corrections

Power struggles

“We need to talk about your choices” conversations

Instead, effective responses focus on de-escalation first.

What this looks like in practice:

Using calm, neutral language

Keeping directions brief and concrete

Offering space or time to cool down

Addressing the issue privately once the student is regulated

Preserving dignity matters.

Students re-regulate faster when they feel safe, respected, and not publicly shamed.

Only after regulation is restored does reflection, accountability, or problem-solving become productive.

THE BIG IDEA FOR TEACHERS

Supporting self-regulation in students is not about lowering expectations.

It’s about recognizing that:

Regulation is developmental

Stress disrupts executive function

Classrooms can either overload or support students’ capacity to cope

When we design classrooms that reduce cognitive load, explicitly teach regulation, rely on supportive structures, and respond calmly to dysregulation, we don’t just manage behavior—we build skills that last.