To Kill a Mockingbird Ch. 2: Scout & Harper Lee’s Letter

Chapter 2 of To Kill a Mockingbird is juxtaposed with Harper Lee’s letter to Oprah Winfrey. The lesson is designed to engage students in a multifaceted exploration of literary devices, thematic parallels, and cultural understandings. Through reading and analyzing selected texts, students will gain deeper insights into character development, societal contexts, and the power of perspective in literature. The lesson plan caters to diverse learning styles by offering a choice of analytical and practical activities. Each activity is meticulously crafted to reinforce students’ comprehension of the novel and to encourage them to apply these insights creatively and critically in today’s world. Whether dissecting figurative language, crafting poignant advertisements, or engaging in reflective discussions, this lesson aims to foster a profound appreciation for literature’s role in shaping and reflecting societal narratives.

Learning Goals

- I will be able to compare Scout’s thoughts on reading in To Kill a Mockingbird with Harper Lee’s views expressed in her letter to Oprah Winfrey.

- I will be able to explain the social and cultural assumptions associated with the Cunningham family in To Kill a Mockingbird.

- I will be able to discuss and respect diverse perspectives as presented in To Kill a Mockingbird.

Materials

Harper Lee’s Letter to Oprah Winfrey

Social Media Ads Template

Process

- Read and discuss Harper Lee’s letter to Oprah Winfrey with the class.

- Read Chapter 2 of To Kill a Mockingbird (Letting students choose which version of the book they prefer)

- Choose one of the following two learning activities

Learning Activity A: Q&A

1. Scout tells us the following about her teacher on the first day of school: “Miss Caroline was no more than twenty-one. She had bright auburn hair, pink cheeks, and wore crimson fingernail polish. She also wore high-heeled pumps and a red-and-white-striped dress. She looked and smelled like a peppermint drop.”

Give two examples of figurative language (literary devices) that Lee uses to describe Miss Caroline.

2. Scout reflects: “Until I feared I would lose it, I never loved to read. One does not love breathing.”

a. What comparison is Lee suggesting in these two sentences?

b. What does it suggest about how Scout thinks about reading?

c. How does this compare with Harper Lee’s letter to Oprah Winfrey?

3. a. When Scout introduces Walter to her teacher by saying, “Miss Caroline, he’s a Cunningham,” what does Scout assume that Miss Caroline will automatically understand about him?

b. What characteristics do the residents of Maycomb automatically associate with “the Cunningham tribe”?

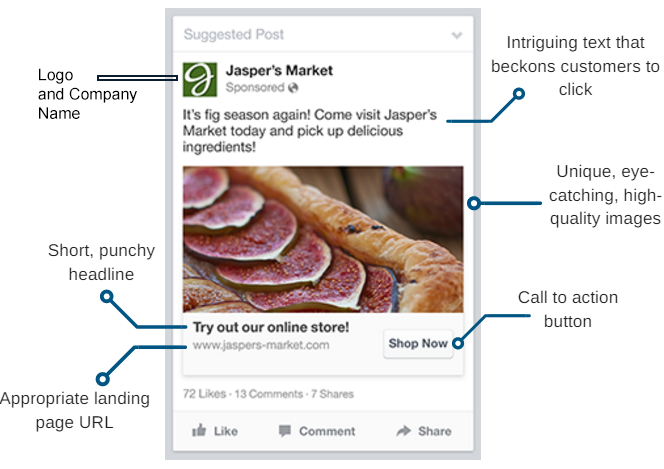

Learning Activity B: Create 3 social media ads

Using the template provided, create 3 social media ads. Follow the guidelines below for each ad. Here are the different parts that make up a social media ad:

Ad #1 – Promote Miss Caroline’s aesthetics in some way. Create a product or service that Miss Caroline might sell. She should be featured in the ad, using this description: “Miss Caroline was no more than twenty-one. She had bright auburn hair, pink cheeks, and wore crimson fingernail polish. She also wore high-heeled pumps and a red-and-white-striped dress. She looked and smelled like a peppermint drop.”

Ad #2 – A product or service related to either:

a. Scout’s quote about reading: “Until I feared I would lose it, I never loved to read. One does not love breathing.”

b. Harper Lee’s letter to Oprah Winfrey and her close connection to reading.

Ad #3 – A public service announcement for all newcomers to Maycomb that helps others understand the Cunninghams. Remember when Scout said, “Miss Caroline, he’s a Cunningham?” What does she assume that Miss Caroline will automatically understand about him? What should she and others know about the Cunninghams?

Assessment

Understanding of Content /10

- Demonstrates a comprehensive understanding of Chapter 2 in To Kill a Mockingbird and Harper Lee’s letter to Oprah Winfrey.

- Accurately identifies and explains literary devices, character perspectives, and thematic elements.

- Shows a clear understanding of the societal and cultural contexts presented in the novel.

Harper Lee’s Letter to Oprah Winfrey

May 7, 2006

Dear Oprah,

Do you remember when you learned to read, or like me, can you not even remember a time when you didn’t know how? I must have learned from having been read to by my family. My sisters and brother, much older, read aloud to keep me from pestering them; my mother read me a story every day, usually a children’s classic, and my father read from the four newspapers he got through every evening. Then, of course, it was Uncle Wiggily at bedtime.

So I arrived in the first grade, literate, with a curious cultural assimilation of American history, romance, the Rover Boys, Rapunzel, and The Mobile Press. Early signs of genius? Far from it. Reading was an accomplishment I shared with several local contemporaries. Why this endemic precocity? Because in my hometown, a remote village in the early 1930s, youngsters had little to do but read. A movie? Not often — movies weren’t for small children. A park for games? Not a hope. We’re talking unpaved streets here, and the Depression.

Books were scarce. There was nothing you could call a public library, we were a hundred miles away from a department store’s books section, so we children began to circulate reading material among ourselves until each child had read another’s entire stock. There were long dry spells broken by the new Christmas books, which started the rounds again.

As we grew older, we began to realize what our books were worth: Anne of Green Gables was worth two Bobbsey Twins; two Rover Boys were an even swap for two Tom Swifts. Aesthetic frissons ran a poor second to the thrills of acquisition. The goal, a full set of a series, was attained only once by an individual of exceptional greed — he swapped his sister’s doll buggy.

We were privileged. There were children, mostly from rural areas, who had never looked into a book until they went to school. They had to be taught to read in the first grade, and we were impatient with them for having to catch up. We ignored them.

And it wasn’t until we were grown, some of us, that we discovered what had befallen the children of our African-American servants. In some of their schools, pupils learned to read three-to-one — three children to one book, which was more than likely a cast-off primer from a white grammar school. We seldom saw them until, older, they came to work for us.

Now, 75 years later in an abundant society where people have laptops, cell phones, iPods, and minds like empty rooms, I still plod along with books. Instant information is not for me. I prefer to search library stacks because when I work to learn something, I remember it.

And, Oprah, can you imagine curling up in bed to read a computer? Weeping for Anna Karenina and being terrified by Hannibal Lecter, entering the heart of darkness with Mistah Kurtz, having Holden Caulfield ring you up — some things should happen on soft pages, not cold metal.

The village of my childhood is gone, with it most of the book collectors, including the dodgy one who swapped his complete set of Seckatary Hawkinses for a shotgun and kept it until it was retrieved by an irate parent.

Now we are three in number and live hundreds of miles away from each other. We still keep in touch by telephone conversations of recurrent theme: “What is your name again?” followed by “What are you reading?” We don’t always remember.

Much love,

Harper

(Sources: FS Blog)

Social Ads Template