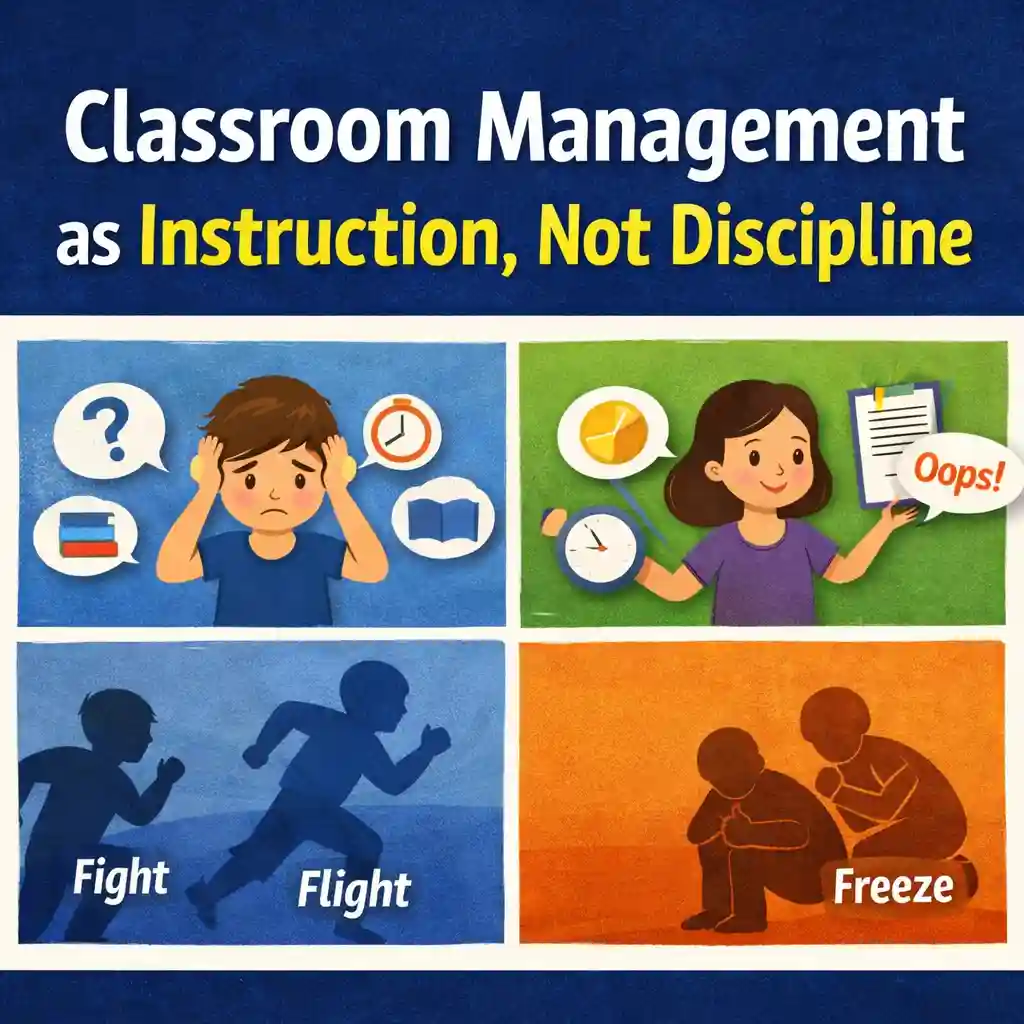

Classroom Management as Instruction, Not Discipline

Most classroom management problems don’t come from students choosing to misbehave. They come from students not being explicitly taught how to succeed in the learning environment. That’s why teachers should attempt to teach classroom management as instruction.

This module reframes classroom management as instructional design rather than discipline. When teachers treat routines, expectations, and behaviors the same way they treat academic skills—modeling them, practicing them, and giving feedback—classrooms become calmer, more predictable, and more humane.

This shift doesn’t lower expectations. It raises them—while giving students the tools to meet them.

Learning Goals

By the end of this module, teachers will be able to:

Explain why classroom management works best when treated as instruction

Identify the limits of discipline-first approaches

Connect classroom management to cognitive science and learning theory

Design and teach routines as explicit lessons

Use a ready-to-go classroom lesson that teaches expectations without shame or punishment

Reframing the Question

Traditional framing:

“How do I get students to behave?”

Instructional framing:

“What skills do students need to function successfully in this learning environment—and how will I teach them?”

This shift matters because students are not born knowing how to do school.

They learn it—or they struggle in systems that assume they already should.

What We Get Wrong About Discipline

Discipline-focused models assume:

Students already know what is expected

Misbehavior is primarily a choice

Consequences teach skills

Research and classroom evidence suggest otherwise:

Many behaviors stem from confusion, stress, skill gaps, or unmet needs

Consequences may stop behavior short-term, but rarely teach replacement behaviors

Punitive systems disproportionately affect marginalized and neurodivergent students

Classroom Management as Instruction: The Core Idea

Classroom management as instruction means:

Teaching routines explicitly

Modeling behaviors the way we model academic skills

Practicing expectations before problems arise

Giving feedback instead of punishment

Viewing behavior as learnable, not moral

This aligns with preventative frameworks like PBIS, relational approaches such as Responsive Classroom, and decades of research in cognitive psychology.

The Science Behind the Shift (Expanded)

1. Cognitive Load Theory: Why Uncertainty Breaks Learning

Cognitive Load Theory, developed by John Sweller, explains that working memory is extremely limited. At any given moment, students are juggling three types of cognitive load:

Intrinsic load – the difficulty of the academic task itself

Germane load – the mental effort used to build understanding

Extraneous load – everything else competing for attention

Classroom management problems live almost entirely in extraneous load.

When students are unsure about:

how to enter the room

when they’re allowed to talk

how to ask for help

what happens if they make a mistake

their brains are burning energy on figuring out the environment instead of learning the content.

Stress multiplies cognitive load

Stress hormones like cortisol directly impair:

attention (students scan for threat instead of information)

working memory (they forget instructions they just heard)

emotional regulation (small frustrations trigger big reactions)

This is why a student who “knows better” may still:

blurt out

shut down

escalate quickly

It’s not defiance—it’s cognitive overload.

Why predictable routines work

Predictable routines:

reduce decision-making fatigue

automate expected behaviors

move actions from conscious effort to habit

When routines are explicitly taught and practiced, they become cognitive shortcuts. Students no longer have to think about how to function—they can devote mental energy to learning.

Key idea:

Calm classrooms aren’t calmer because students are more compliant—they’re calmer because students aren’t overloaded.

2. Executive Function Development: Skills We Assume Instead of Teach

Executive function refers to a set of brain-based skills that manage behavior and learning, including:

Self-regulation (managing emotions and impulses)

Task initiation (getting started without avoidance)

Working memory (holding steps in mind)

Cognitive flexibility (shifting strategies when stuck)

These skills are not fully developed until the mid-20s—and they develop unevenly.

Adolescents may:

understand expectations intellectually

but lack the neurological wiring to consistently meet them under pressure

This gap is where most “behavior problems” live.

The school contradiction

Schools often:

demand high-level executive skills

while offering minimal direct instruction in those skills

For example:

“Be responsible” (without defining what that looks like)

“Stay on task” (without scaffolding task initiation)

“Make good choices” (without teaching regulation strategies)

When executive skills are assumed instead of taught:

students internalize failure

teachers misinterpret struggle as resistance

Instructional management fixes this mismatch

Treating classroom management as instruction means:

breaking expectations into steps

modeling self-regulation strategies

rehearsing transitions

teaching students how to recover after mistakes

This doesn’t excuse behavior—it builds capacity.

Key idea:

You can’t discipline a skill into existence. You have to teach it.

3. Trauma-Informed Research: Behavior as Survival, Not Disrespect

Trauma-informed research shows that students exposed to chronic stress, adversity, or instability may operate in a heightened survival state.

This includes students affected by:

family instability

poverty

discrimination

ongoing anxiety

past or present trauma

(And yes—this is more common than many educators realize. Large-scale studies like the ACEs research, supported by organizations such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, highlight how widespread these experiences are.)

The nervous system under threat

When students perceive threat—real or perceived—the brain prioritizes survival over learning. This often looks like:

Fight – arguing, aggression, refusal

Flight – avoidance, leaving seat, skipping work

Freeze – shutdown, silence, disengagement

Importantly:

These responses are automatic

They are not conscious choices

They bypass the rational part of the brain

This is why punitive responses often escalate behavior instead of improving it.

Why clarity and routine are regulating

For students in survival mode, predictable routines act as external regulation.

Clear instruction and consistent structures:

signal safety

reduce uncertainty

lower the brain’s threat response

This doesn’t mean classrooms should be rigid or authoritarian. It means they should be reliably structured.

Examples of regulation-supportive practices:

knowing exactly how class starts

predictable responses to mistakes

neutral, calm language from adults

clear paths for repair after conflict

These supports help students return to a learning-ready state.

Key idea:

Structure is not control—it’s safety made visible.

Pulling It All Together

Across cognitive science, developmental psychology, and trauma research, the message is consistent:

Uncertainty increases stress

Stress reduces learning

Instruction reduces uncertainty

When classroom management is treated as instruction:

cognitive load decreases

executive skills grow

nervous systems settle

And when those things happen, behavior improves without punishment becoming the centerpiece.

What Instructional Management Looks Like in Practice

| Discipline Model | Instructional Model |

|---|---|

| Rules posted once | Routines taught, practiced, revisited |

| Consequences first | Feedback and reteaching first |

| Public correction | Private coaching |

| Compliance-focused | Skill-focused |

| Reactive | Preventative |

Teaching Routines Like Academic Content

If we wouldn’t say,

“I explained essay writing once—why can’t they do it?”

we shouldn’t say the same about behavior.

Instructional approach to routines includes:

Naming the routine

Explaining why it matters

Modeling it

Practicing it

Giving feedback

Revisiting as needed

Ready-to-Use Classroom Lesson

Teaching Classroom Expectations as Instruction

Grade Level: Adaptable (Grades 4–12)

Time: 30–45 minutes

Purpose: Teach classroom expectations as shared skills—not rules

Lesson Objective

Students will:

Understand why routines exist

Identify behaviors that support learning

Practice expectations collaboratively

Reflect on how structure supports success

Materials

Chart paper or slides

Markers

Reflection handout (optional)

Step 1: Framing the Lesson (5 minutes)

Teacher script (adapt as needed):

“In this class, we’re going to treat how we work together the same way we treat academic skills. That means we don’t assume everyone already knows how to do school—we learn it together.”

Emphasize:

This is not about control

This is about making learning easier

Step 2: Co-Constructing Expectations (10 minutes)

Ask students:

“What helps you learn?”

“What makes it hard to focus?”

“What should this room feel like when learning is happening?”

Record responses.

Group them into 3–5 broad expectations (e.g., Respect time, Respect learning, Respect people).

Step 3: Making Expectations Concrete (10 minutes)

For each expectation, ask:

“What does this look like?”

“What does it sound like?”

“What does it look like during group work?”

This step turns abstract values into observable behaviors.

Step 4: Modeling & Practice (10 minutes)

Choose one routine (e.g., entry routine, group work, asking for help).

Model it correctly

Model it incorrectly (briefly, humor helps)

Have students practice

Give feedback

Normalize mistakes:

“Practice is how skills grow.”

Step 5: Reflection & Buy-In (5–10 minutes)

Reflection prompts:

Which expectation will help you most this year?

What support do you need from me?

What should I do if something isn’t working?

This reinforces shared responsibility, not compliance.

Why This Works Better Than Discipline

Students know what success looks like

Teachers spend less time correcting

Behavior issues decrease because confusion decreases

Relationships improve because shame decreases

Learning time increases

This approach doesn’t eliminate consequences—but it dramatically reduces the need for them.

Common Teacher Concerns (And Reframes)

“This takes too much time.”

→ Reteaching behavior all year takes more.

“Students should already know this.”

→ Knowing ≠ doing under stress.

“I’ll lose authority.”

→ Teaching builds credibility, not weakness.

Reflection for Teachers

Which routines do I assume students know?

Where do I correct instead of teach?

How might instruction reduce friction in my classroom?

Key Takeaway

Classroom management works best when it’s treated as part of instruction—not a response to failure.

When we teach students how to function in learning spaces, behavior stops being a battleground and becomes another place where growth is possible.

Next: How Stress, Emotion, and Cognition Affect Behavior (Coming Soon)