In this lesson, we’ll look at ancient Greek mythology, examining the grand tapestry of the Greek creation myth alongside the enigmatic legend of Theseus and the Minotaur. Our exploration will prompt us to sift through layers of allegory and historical speculation: What truths might lie beneath these ancient narratives that shaped the Greeks’ understanding of the world? As storytellers and seekers of wisdom, the Greeks wove tales of gods and heroes to make sense of the cosmos and their place within it. Through discussion and critical analysis, we will ponder the line between myth and potential historical fact, the intent behind these creation stories, and the possible realities they masked or revealed.

Learning Goals

- I will be able to interpret and discuss the symbolic and thematic significance of the Greek creation myth and the story of Theseus and the Minotaur, assessing their narrative structures and literary elements.

- I will be able to evaluate the role of myth in literature by exploring the intentions behind the Greek myths, recognizing how they convey ancient Greek societal values, moral lessons, and human experiences.

- I will be able to compose a reflective journal entry that articulates my analysis of the myths, employing critical thinking to distinguish between the figurative language of myth and potential historical underpinnings.

Materials

Process

- Discuss the Greek creation story. Ask the students if some of it could be true or what might have inspired these stories.

- Present background information on the Island of Crete, bull-worshipping, and the Palace of Knossos.

- Have students read the “Theseus and the Minotaur” myth.

- Ask students to write about which elements of the story they believe might be true, which are myth, and what might have happened.

Assessment

Journal Question

Reflect on the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur, considering both the tale itself and the discussion we had in class. In at least one well-developed paragraph, discuss which elements of the story you think could be based on historical truths and which aspects seem to be purely mythological. Use specific examples from the myth to support your opinions. Additionally, consider why the ancient Greeks might have blended fact with fiction in this tale. What purposes do you think these mythical narratives served in their society?

The Purpose of Creation Myths

The purpose of a creation story is multifaceted, serving not only as a means of explaining the origins of the world and humanity but also fulfilling cultural, religious, social, and psychological functions within a community. Here are some of the key purposes of creation stories:

Cosmological Explanation: Creation stories provide an explanation for how the universe, Earth, and life came into being, offering answers to fundamental questions about the origin of everything.

Cultural Identity: They often form an essential part of a society’s mythos, contributing to a shared sense of identity and heritage among its members.

Moral Framework: Many creation myths also establish a moral code or the basis for what is considered right and wrong within the culture, often through the actions of deities or primordial beings.

Religious Beliefs: They frequently reflect and reinforce the religious beliefs of a community, describing the nature of the divine and the relationship between the divine and the mortal world.

Educational Tool: These stories are used to pass on knowledge, traditions, and values from one generation to another, teaching younger members about the beliefs and practices of their community.

Social Order and Structure: Creation myths can legitimize a society’s social structure by explaining the origins of important social institutions, such as the family, leadership hierarchies, and social roles.

Understanding Natural Phenomena: They often explain natural occurrences (like thunderstorms, earthquakes, the cycle of seasons) through stories, attributing them to the actions of gods or cosmic forces.

Psychological Comfort: On an individual level, creation stories can offer comfort and a sense of place in the universe, helping people to understand their role in the world and providing a context for their existence.

Philosophical Inquiry: They encourage exploration of existential questions, such as “Why are we here?” or “What is our purpose?” providing a platform for philosophical discussion.

Symbolic Language: Creation myths are often rich in symbols and allegory, offering a language through which people can discuss complex ideas about existence, creation, and the human condition.

The Greeks and Creation

The Greek creation myth, or cosmogony, is a rich and complex story that outlines the origin of the cosmos and the gods. There are several versions, but one of the most comprehensive accounts is found in Hesiod’s “Theogony,” which can be summarized as follows:

Chaos and the Primordial Deities

In the beginning, there was only Chaos, a void or chasm of nothingness. From Chaos emerged the first primordial deities:

Gaia (Earth): The solid ground, the foundation of all life.

Tartarus: The deep abyss used as a dungeon of torment and suffering for the wicked and as the prison for the Titans.

Eros (Love): The force of attraction and procreation that would become the means to bring beings into existence.

Erebus (Darkness): The personification of the deep darkness and shadows.

Nyx (Night): The embodiment of the night.

The Birth of the Titans

Gaia alone gave birth to Uranus (the Sky) who then became her consort, covering her on all sides. Together, they produced the twelve Titans, the three Cyclopes, and the three Hecatoncheires (hundred-handed ones). The Titans included well-known figures like Cronus and Rhea.

The Rule and Overthrow of Cronus

Uranus, fearing the power of his children, imprisoned them in Tartarus. Angered by this, Gaia conspired with her youngest Titan son, Cronus, to overthrow Uranus. Cronus castrated Uranus, and from his blood came other deities and monsters, including the Giants, the Furies, and the Meliae (nymphs of the ash tree).

Cronus, having overthrown his father, took Rhea as his wife, but he also feared a prophecy that he would be overthrown by his own child. As a result, whenever Rhea gave birth, Cronus swallowed the child. However, when their youngest child, Zeus, was born, Rhea tricked Cronus by giving him a rock wrapped in swaddling clothes to swallow instead.

The Rise of Zeus and the Olympian Gods

Zeus was raised in secret and eventually challenged Cronus, forcing him to regurgitate his siblings: Poseidon, Hades, Hestia, Hera, and Demeter. This led to the Titanomachy, a ten-year war between the Titans, led by Cronus, and the Olympians, led by Zeus. The Olympians, with the help of the Cyclopes and the Hecatoncheires, emerged victorious.

The Creation of Humanity

After the fall of the Titans, the world was divided among the three brothers: Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades, ruling the sky, the sea, and the underworld, respectively. Humanity was created—though accounts of their creation vary—with some myths attributing their creation to Prometheus, a Titan who defied Zeus by giving humans fire.

Establishment of Order

With Zeus as the king of the gods and Olympus, a new order was established. The various gods and goddesses took on roles and domains, interacting with each other and with humanity, leading to the countless myths and legends that comprise Greek mythology.

This creation myth set the stage for the pantheon of gods and the tales that would be told for generations, embodying the values, fears, and aspects of the world as the ancient Greeks understood it.

Is Theseus More than a Myth?

The myth of Theseus and the Minotaur captivates us with its blend of heroic adventure and mythical elements, yet within its tapestry, there may lie strands of historical truth. The labyrinthine palace of Knossos, for instance, is a real archaeological site on Crete, suggesting that the setting of Theseus’s tale was inspired by an actual place.

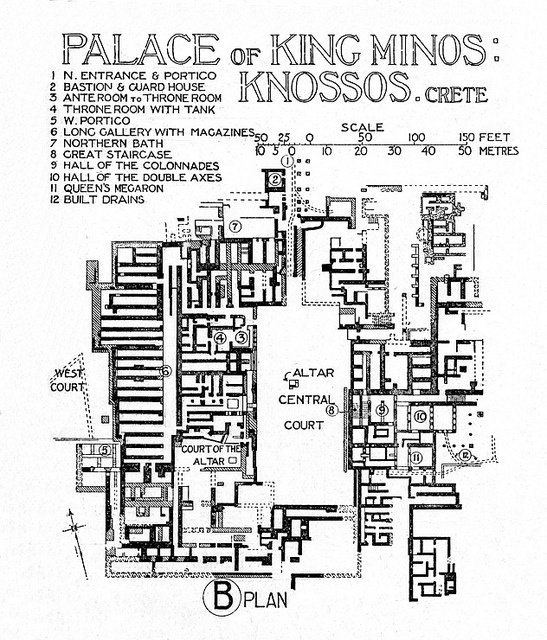

The archaeological site of Knossos, situated on the Greek island of Crete, is one of the most significant and evocative discoveries related to ancient Minoan civilization. Excavated by Sir Arthur Evans in the early 20th century, the complex is believed to be the legendary palace of King Minos and is often associated with the myths of the Minotaur and Theseus. Knossos is an expansive ruin, with an intricate layout that some have likened to a labyrinth, providing a tangible connection to the famous myth. Its frescoes, architecture, and artifacts have offered invaluable insights into Minoan culture and have spurred debates on how much the myths derived from the ceremonies, rituals, or events that may have taken place there.

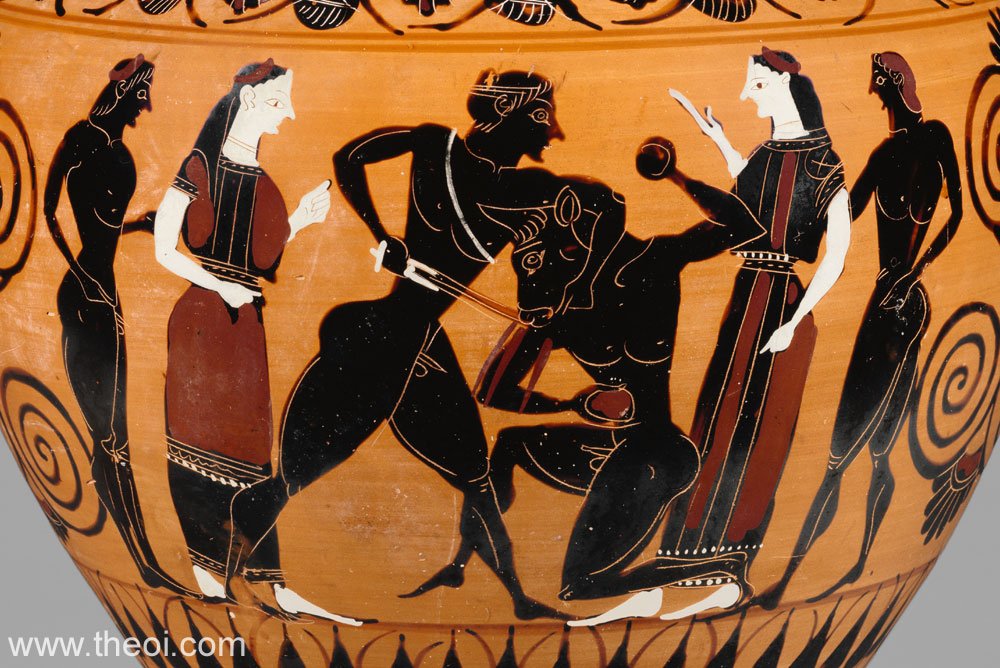

Furthermore, the story’s Minotaur, a half-man, half-bull creature, might symbolically represent Minoan bull-worship or the bull games of ancient Crete. It’s possible that Theseus’s character is an embellished memory of a real person, a leader or hero whose feats grew into legend over time. While we may never fully separate fact from mythic embellishment, these potential truths serve as tantalizing hints that history and myth are intricately woven together in the legacy of Theseus and the Minotaur.

Theseus and the Minotaur Story

Minos, king of Crete, had a monstrous son with the body of a man and the head of a bull. He was called the Minotaur. He was kept in a maze of tunnels, a twisting labyrinth underneath the king’s palace. The creature would only eat human flesh. The king knew that, if he were to feed the monster with his own people, they would rise up against him. But the creature was his own son, of royal blood. He couldn’t let him starve to death. What was he to do?

One of his advisers said, ‘Many nations fear you, your majesty. You must demand that each kingdom send seven young men a year.’

And so it was. Each kingdom of Greece was forced to send seven young men, seven young men who would never be heard of again. Rumours travelled from Crete with trading ships, rumours of a flesh-eating beast beneath Minos’ palace.

When the turn of Athens came, the city’s king couldn’t bring himself to send seven young Athenians to a horrible death. He delayed and delayed. Eventually, King Minos, furious, set sail himself with a fleet of ships and, when the people of Athens saw the ships of King Minos slicing through the waves, every man woman and child shuddered. They’d heard stories about Minos’ monstrous son and the word ‘Minotaur’ had been whispered from mouth to ear. What was more, the last time Minos had visited the city he had taken the inventor, Daedalus, and the boy, Icarus. Father and son had never been seen again.

As soon as the ships reached the quayside, King Minos and his soldiers leapt ashore. They marched through the streets and, wherever the king saw a young man of noble bearing, he would shout ‘Seize him!’ Six young men had been taken when they reached the palace of King Aegeus, the king of Athens. Standing behind the king’s throne there was a beautiful young man with a crown of laurel leaves on his head. He looked like a god. He could almost have been Ares, the beautiful god of war.

King Minos lifted his arm and pointed: ‘He will be the seventh.’

King Aegeus fell to the ground at Minos’ feet. ‘Please, he is my own son, my only son, Theseus. I beg you, spare his life!’

Minos kicked the king aside. ‘Seize him.’

The seven Athenian youths were bundled aboard a Cretan ship. For three days and nights they sailed. When they reached the island of Crete, they were led to the king’s palace by a glittering procession. They were invited to sit down to a feast. But as they tasted the savoury meats and sipped the sweet wines, they could hear the sound of keys turning in locks and they knew they were trapped.

That night they slept on silken sheets under purple blankets; but the next morning there were only six of them at the breakfast table. As they ate, they heard the distant sound of screaming from somewhere far below. Five pushed their plates away but Theseus chewed his food and listened, a strange half-smile playing across his face.

King Minos entertained his guests. The finest Cretan runners, leapers, wrestlers and archers were invited to compete with the Athenians. Theseus defeated every one of them. And in the evenings, the king’s daughter, Princess Ariadne, would dance for them. She wore a crown that burst into flickering flames if stone was struck against iron. It made the shadows of the hall dance alongside her.

And then, one morning, there were five of them at the breakfast table, and then there were four. Ariadne couldn’t take her eyes off Theseus. When he was running or wrestling, she would be watching him. When she was dancing, her eyes were fixed on him. Theseus felt the weight of her gaze and smiled to himself. Then there were three of them at the breakfast table. And then two. When no one was watching, Theseus seized Ariadne’s hand: ‘Ariadne, from the moment I first saw you I have loved you.’

She looked at him and tears trickled down her cheeks. She shook her head, pulled her hand away and ran out of the hall. And then, one morning, Theseus found that he was alone at the breakfast table.

He waited for his chance and then approached Ariadne again. He whispered, ‘Ariadne, is there nobody who could help me? If I could escape I would take you with me.’

Ariadne couldn’t help herself. She melted into his arms; she pressed her lips to his lips. ‘Yes, yes. There is someone.’

That night she crept out of the palace and placed, just inside the maze, the things Theseus would need to kill her monstrous brother. Then she tiptoed into Theseus’ bed-chamber. She leaned over the bed. ‘My love, when they take you to the labyrinth, feel amongst the shadows to your left. You will find my crown to light your way; you will find a ball of golden thread so that you won’t get lost; and you will find a bronze sword for my brother. I will be waiting for you outside.’ She kissed him and slipped away.

The next morning King Minos was amazed. Theseus came out of his bedroom of his own free will – no need to drag him screaming. Surely by now he understood his fate? He was cracking jokes with the guards! Down to the maze they went. The darkness swallowed him and there was silence.

Theseus felt among the shadows, his fingers closed around Ariadne’s crown. He lifted it onto his head. He felt for the iron and stone, and struck them together. The crown blazed with light and now he could see. He tied the end of the ball of golden thread to a snag of rock. He picked up the bronze sword. He began to make his way into the labyrinth, unravelling the thread as he went. He wound to the left and to the right. Above his head, the shadows danced. Below his feet, there were shreds of rag and splinters of bone, picked clean.

Then suddenly, he could hear it, grunting and snorting. And then he could smell it, the sour smell of stale sweat and the sickly sweet stench of rotten flesh. Then he rounded a bend and saw it – the human body, the great bull head: the Minotaur. The monster was filled with terror. His night sight had never endured such brightness before. He lurched and lost his balance, blinded. Theseus laughed.

This was easy! He plunged his sword into the beast’s belly. The Minotaur dropped to his hands and his knees, felt something pierce his skin over and over. He wanted to beg for mercy but no one had taught him the words with which to speak. He screamed. Again and again, Theseus stabbed the Minotaur. He stabbed its neck, its arms, its thighs, its chest. He opened up a constellation of wounds. It sank to its knees. He seized one of its horns and he hacked of its head. Then he wound in the golden thread and followed the tunnels to right and left, dragging the head behind him.

At last he saw the entrance. He crouched and waited until the night came. Ariadne was waiting outside. When the stars were shining, Theseus came out of the labyrinth and lifted the great bull head. He thrust it onto a stake. Then he seized Ariadne’s hand and they ran to the harbour. They jumped onto the deck of a ship; they cut the ropes and sailed away. But before they left the harbour they set fire to the fleet of Cretan ships so that a black pall of smoke rose into the sky, extinguishing the lights of the stars.

Ariadne had never been so happy. Every night Theseus would whisper promises into her ears. ‘Such wealth, such happiness will be ours when you become a queen of Athens.’ After several days they came to the island of Naxos. Theseus suggested they go ashore for fresh meat and fresh fruit. And that night they lit a fire on the beach. They ate; they talked; they laughed; they danced in the firelight.

Then they slept in the warmth of the embers.

In the middle of the night Ariadne woke. She was alone. She sat up and looked about herself. By the light of the moon she could see the ship. She could see the anchor chain was being lifted. She could see the sails were being unfurled. She ran down to the water’s edge. ‘Theseus!’

From the deck of the ship came the sound of laughter – cold, hard laughter. ‘Sister of a bull, these were all you gave me that were worth anything. Take them back.’

There was a thud behind her, and then another, and then a third. She turned and saw her crown, the ball of golden thread and the bronze sword, lying on the sand. ‘Sister of a bull, ponder this as you wander the coast of Naxos, bellowing and blaring. I never loved you. I never ever loved you, and now I am free to forget you.’

The wind filled the sails, the prow of the ship sliced through the waves, and Theseus was gone.

Ariadne dropped to her knees. She buried her face in her hands and trembled with sobs. But nothing is hidden from the eyes of the mighty gods. Dionysus, the god of drinking and drunkenness, wild music and wild dancing, he saw her and he felt pity stirring in his heart. He came striding down from the heavens and lifted her to her feet. ‘Ariadne,’ he said, ‘forget Theseus’ empty promises to make you a queen of Athens. I will make you a queen of the heavens.’ He lifted up her crown and it burst into flames. He reached high above his head and set it in the heavens as a constellation, a circlet of shining stars. Then he led her up to his palace, on the high slopes of Mount Olympus, where she became his consort, his queen. And ever since then, we’ve been able to see her crown in the sky. Sometimes we call it the Pleiades.